The following analysis of Syria, from a left-wing perspective of support for the anti-fascist democratic revolution there, is republished with permission from the site Democratic Revolution, Syria style. “The revolution is the negation of the regime and Daesh is the negation of the revolution”. It was published there on 1 August 2014.

* * * *

The Leviathan built by Hafez al-Assad, a fascist state stretching from Daraa in the west of Syria to Deir Ezzor in the east, has been shattered irrevocably by thepopular upsurge of the March 15 revolution. Born as a peaceful protest movement for dignity and political reform, the Syrian uprising painfully and organically developed into a revolutionary war to liberate the country from the misrule of Bashar al-Assad’s fascist clique and dismantle his regime’s barbaric institutions.

Like all wars, this war in the final analysis is a class war. Suburban and rural (mostly Sunni) farmers, laborers, small merchants, and elements of big business fight to overthrow their enemies, the urban-based Alawite-dominated state apparatus, that apparat‘s junior partners — the Alawite, Sunni, and Christian bourgeoisies — as well as its Iranian, Iraqi, and Hezbollah enablers. Unfortunately, these enemies do not fight alone: educated professional urban Sunnis constitute the backbone of the civil service bureaucracy that keeps the regime running and some 15%-20% of the adult male Alawite population serve in the military-security services. Those who have nothing to lose find themselves in combat fighting those who have nothing to lose but their chains. The have-nots fight for freedom while the have-littles fight for fascism.

________________________________________

“Who do you feel best represents the interests and aspirations of the Syrian people?”

Monthly

Household

Income Regime Opposition Extremists

Less than 15,000 SYP 31% 37% 12%

15,000-25,000 SYP 33% 35% 15%

25,001-45,000 SYP 39% 38% 14%

More than 45,000 SYP 36% 37% 13%

Education

Level

Completed Regime Opposition Extremists

No Formal 33% 37% 13%

Primary 38% 32% 13%

Intermediate 35% 32% 14%

Secondary 31% 40% 11%

Higher 40% 38% 14%

Source: Orb International.

________________________________________

The anti-fascist democratic revolution that emerged out of the contradictions of Syria’s sect-class system has spawned a sect-class war that spread far from the city of Daraa where the uprising first gained traction to Lebanon, Iraq, Turkey, and Kurdistan. The peoples of the whole region are now paying the price for:

1. The sins of Assad and his supporters.

2. The revolution’s inability to defeat and remove them from power.

3. The terrorist-creating policies of the U.S.-led so-called ‘Friends of Syria‘ who shamefully allowed themselves to be out-spent, out-gunned, out-maneuvered, and out-committed by Iran at every turn for more than three years because they prefer military stalemate as a means of engineering a negotiated settlement over an outright rebel victory.

These three factors have protracted Syria’s war of liberation and led to what Marx termed “the common ruin of the contending classes” – $144 billion in economic losses in a country whose 2011 GDP was $64 billion, 50% unemployment (90% in rebel-held areas), 50% in dire poverty, rampant inflation, polio outbreaks among children, and 9 million (almost half the population) displaced with 3 million living in camps abroad.

And there is no end in sight to this unfolding disaster.

The increasingly protracted nature of Syria’s anti-fascist war has transformed groundless optimism among the revolution’s supporters into its opposite: cynicism. Conversely, Assad is confident that his regime is no longer in danger of being overthrown. Both trends in both camps stem from the regime’s string of strategic military victories — in summer of 2013 at Qusayr, in fall of 2013 at Safira, in March 2014 at Yabroud, and in April 2014 at Qalamoun. However, military momentum alone cannot reveal who the victor and vanquished will ultimately be. Only by analyzing the strong and weak points that characterize each side and how those points have changed during the course of the war can reveal who can win and how.

Regime Strong Points:

o Firepower.

o Unity and united, effective leadership.

o Allies abroad — few, but fully committed.

o Victory means successfully defending territories (cities, main roads; some 40% of the country) that are its strongholds.

o Resources (financial, economic, infrastructure [electricity]).

o Fights along interior lines.

o Majority of minorities’ support, minority of majority support.

Regime Weak Points:

o Unjust cause.

o Popular support based on opportunism (‘who will win? who will pay me?’), not conviction.

o Manpower.

o Fighters motivated more by fear, circumstance, and money than ideology or conviction.

o Parasitic dependence on foreign allies.

o Oil-producing and agricultural areas, the principal sources of hard currency and economic viability of the pre-2011 regime, no longer under regime control.

o Gulf state investment and tourism that fueled the Bashar-era economic boom gone for the foreseeable future.

Rebel Strong Points:

o Just cause.

o Fighters motivated by conviction and religious fervor (‘God is on my side‘) rather than opportunism.

o Manpower.

o Popular support based on conviction, not opportunism.

Rebel Weak Points:

o Firepower.

o Disunity and divided, ineffective leadership(s).

o Allies abroad — many, but non-committal.

o Victory means launching successful offensives to oust regime from its well-defended strongholds where it retains significant popular support.

o No coherent economic or cultural policies, liberated areas poorly governed.

o No resources despite wresting oil-producing and agricultural areas from regime’s grip.

o Dependent on non-committal allies abroad for aid and support.

o Fights along exterior lines.

o Minority of minorities’ support, majority of majority’s support.

A ‘New’ Regime, Born Fighting the Revolution

The old regime fought to crush the uprising and disintegrated amid defections of its troops and officials throughout 2011 and 2012 thereby creating a ‘new’ regime. Regime 2.0 is a leaner, meaner, defection-free killing machine whose war-fighting is characterized by strategic vision, methodical prioritization, and a disciplined command structure steady enough to guide campaigns over weeks and months to victory. Whereas regime 1.0 fought to obliterate the uprising in all areas at once, regime 2.0 picks and chooses its offensives and seeks to buy ever-more time to gain ever-more advantages over the rebels. Its military strategy is to hold onto the cities, highways, and airbases — even at the cost of leaving the suburbs and the countryside to the rebels — while organizing a series of strategic offensives to clear the core of the country (stretching from Daraa to Aleppo) of rebel fighters, forcing them to the periphery and reducing their status from major threat to manageable nuisance. Its political strategy is to prevent opposition forces from gaining popularity. This is accomplished through two mechanisms: make the price of defying the regime so high that no city or large town will dare join the revolution of its own volition and make governance (let alone good governance) in liberated areas impossible. The emergence of free Syrian territories where the hungry are fed, the sick are cared for, and where law and order prevail without a massive apparatus of torture and terror would threaten the reluctant, grudging support people give the regime as a lesser or necessary evil. This two-fold political strategy is why the regime relentlessly attacks targets of no military value like hospitals, bakeries, and schools while airstrikes on the Islamic State (formerly ISIS/ISL, known pejoratively as Daesh) have been rare (see below) up until recently.

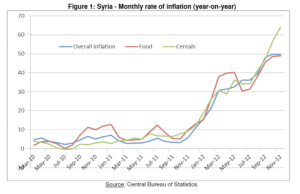

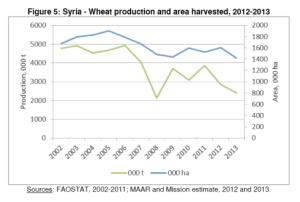

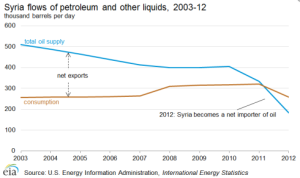

The post-revolution Assad regime is significantly weaker than its 2011 precursor despite its seeming immunity to defections and lower threshold for victory. Its chemical weapons arsenal is gone. Less than 50% of the country is under its control. Most importantly, having permanently lost control over the wheat, cotton, and oil-producing rural north and east, the regime is no longer economically viable. Regime 2.0 is a militarily robust failed state in the making. Wheat production has fallen dramatically, centralized state purchase of grain from farmers has given way to localized transactions, inflation is spiraling out of control, industry has ground to a halt, children begging on the streets of the capital Damascus is now commonplace, oil production (one of the few sources of hard currency for the regime) has all but ended, Syria has become a net oil importer even as its oil consumption has fallen, and widespread food shortages afflict rich and poor alike.

________________________________________

“Which of the following have you had a shortage of in the last six months?”

Monthly

Household

Income Electricity Food Water

Less than 15,000 SYP 74% 56% 40%

15,000-25,000 SYP 76% 49% 44%

25,001-45,000 SYP 74% 51% 42%

More than 45,000 SYP 78% 47% 43%

Source: Orb International.

________________________________________

The post-revolution regime is not only living on borrowed time but borrowed money — mainly Iran’s. However, it is unlikely that Damascus will ever repay even a fraction of the over $10 billion and counting Tehran spent saving Syrian national socialism from reaching a tipping point of no return during the armed rebellion’s peak in late 2012 and early 2013. Iran’s rulers will learn the hard way what France, Britain, and the U.S. discovered in the 20th century: that colonies and protectorates are expensive and prohibitively so from the standpoint of return on investment.

One new feature of the post-revolution regime is that Assad no longer wields absolute power. He answers to not only Iran and Hezbollah but to his generals (who now enjoy some command autonomy unlike before the revolution) as well as to the newly created Iranian/Hezbollah-trained National Defense Forces (NDF). Assad’s diminished authority became evident during Geneva 2 in two respects: first, Russia compelled the regime to attend talks it spent years rejecting in under 24 hours and second, the NDF continued shelling Homs despite the deal Assad made with the United Nations (UN) to evacuate civilians from besieged neighborhoods. During the evacuation conducted under UN supervision, Homs governor Talal al Barazi screamed at NDF members for abusing and interrogating evacuees in plain sight: “What’s wrong with you? This is the United Nations. We have been getting calls from Geneva!” Similarly, when the 2,000 heroes of Homs were evacuated in May 2014, UN personnel were placed on each vehicle filled with rebels to prevent the NDF from shelling their exit and sabotaging the deal which included a prisoner exchange.

So while Assad’s reliance on a few but firm allies is a source of strength against the rebels whose allies are many but mealy-mouthed, it has also become a weakness since his regime has grown parasitically and permanently dependent on their financial, military, and political life support. Russia exercised its growing leverage over the embattled regime by forcing Assad to surrender the bulk of his prized chemical weapons stockpile in order to avoid airstrikes, the threat of which not only halted the regime’s barrel bombing but also triggered a spike in defections. A U.S.-led air campaign would have tipped the battlefield balance towards the rebels for as long as it lasted and both Russia and Iran were determined to avoid the possibility of the regime’s irrevocable disintegration and defeat. The price of the regime’s survival was Assad’s sarin supply and his foreign overlords were happy to pay it.

Thus, Assad has fallen from his 2011 position as Führer to that of a governor of an Iranian semi-protectorate rife with quasi-independent militias that often victimize regime supporters. Just as the Assad family uses their Alawite co-religionists as human shields for their rule, Iran uses Syria for its operations against Israel. In a historic shift from Hafez’s policy of keeping his side of the Golan Heights quiet, Bashar and Hezbollah recently launched token attacks on Israel from the Golan, triggering Israeli retaliation. In this way, Iran opened a second (insignificant) front against Israel during Israel’s 2014 attack on another recipient of Iran’s aid, Hamas, and demonstrated that Syrian independence is increasingly a thing of the past.

A Second Revolution or War of Mutual Exhaustion?

Can the post-revolution Assad regime be overthrown? Could a second revolution break out behind regime lines and finish what Daraa started? Such an uprising is an objective possibility given the simmering, casualty-driven discontent among Alawites but highly unlikely because it would have to take the form of an armed uprising from the outset since a peaceful uprising against a fascist regime at war is impossible. As long as the war — which suppresses dissension among the regime’s remaining supporters — continues with virtually unlimited foreign economic, political, and military support from abroad, the regime can avoid another revolution, that is, “the violent break-up of [an] obsolete political superstructure, the contradiction between which and the new relations of production caused its collapse at a certain moment” (Lenin) that often follows when a political superstructure’s economic basis has ceased to exist.

Without a second revolution to topple the post-2011 regime, Syria’s revolutionary war of liberation has become a protracted struggle of attrition, a contest of mutual exhaustion and mutual annihilation. The strategic equilibrium or stalemate between regime and rebel forces will persist until one side either organizes a series of decisive offensives to gain total victory or collapses out of exhaustion brought about by its own internal contradictions.

The fact that a second revolution or war of quick decision to defeat the regime is not an immediate prospect is not necessarily grounds for despair. The regime enjoys material superiority over the revolution but not moral superiority. The unjust and reactionary nature of the regime and its war aims gives rise to its critical weakness: its manpower shortage. Not enough Syrians are willing to die for fascism; those that are willing tend to either be morally rotten criminals eager to get a salary for raping, looting, and torturing their countrymen or conscriptswho fear imprisonment and torture for draft-dodging. These criminal and cowardly elements have difficulty sustaining close combat with rebels who fight not for personal gain but out of conviction that their cause is just and that God is on their side. So few Syrians are motivated to charge into battle and lay down their lives for tyranny and oppression that some 10,000 Iranian, Hezbollah, and Iraqi sectarian Shia militiamen were imported to serve as the regime’s shock troops. Once sectarian killing spread to Iraq, Iraqi Shia militiamen returned home to kill Sunnis, creating a manpower shortage for Hezbollah whose idea of ‘resisting‘ Israel is slaughtering Syrians and starving Palestinians on Assad’s behalf.

The moral bankruptcy of the regime finds expression in its war-fighting methods: heavy on firepower, light on manpower (save for strategically critical offensives to regain lost ground). Because the regime cannot afford to lose manpower in head-to-head combat with rebel forces, it demolishes neighborhoods, resorts to barrel bomb terrorism, starves women and children, uses Scud missiles and sarin, and signs starvation truces and evacuation deals with rebel neighborhoods instead of invading them and ousting the fighters. Free Aleppo was forcibly de-populated using these methods with the aim of destroying rebel manpower by depriving them of their popular base of support. Without the people standing firmly behind and among them, isolated rebels can be defeated with superior firepower.

Unity: A Do-or-Die Task for the Revolution

To fight — much less win — a war with these characteristics, the key strategic imperative for the rebels is not to seize and hold territory (as in conventional war) but to annihilate enemy manpower (as in guerrilla war). Territory changes hands day to day, month to month with every skirmish and battle, but available manpower ultimately determines who is capable of controlling what.

However, to take advantage of the regime’s key weakness (manpower) and turn the tide of the war once more in their favor, the rebels must overcome their key weakness — lack of unity (and related to this, poor leadership).

Rebel disunity has been the single most powerful weapon in Assad’s arsenal. Time and again, this disunity has allowed the regime to capitalize on its strong points and minimize its weak points while simultaneously neutralizing rebel strong points and magnifying rebel weak points. Consider the rebel response to each regime offensive since June 2013:

o At Qusayr, some reinforcements came from as far as Aleppo to fight the offensive head-on. The regime’s superior firepower and massed manpower overwhelmed the city’s defenders. Shock swept opposition circles even though the battle, as a head-on clash between a stronger and a weaker force, could not have ended in anything other than a regime victory. A counter-offensive elsewhere to relieve pressure from Qusayr or weaken the regime’s attack was never an option because rebels were too divided.

o At Safira, there was no rebel effort to resist or counter the regime’s advance. It fell without a fight, giving the regime a beach head to push rebel forces out of Aleppo. Colonel Abdul-Jabbar al-Aqidi resigned from his position on the Free Syrian Army’s (FSA) Supreme Military Council to protest the rebels’ failure to lift a finger to defend the city.

o At Yabroud and Qalamoun, rebel forces massed to resist the regime’s offensive. Knowing that head-on, open-ended resistance would end in defeat and the total destruction of their forces, they followed Mao Tse-Tung’s principles for guerrilla operations: “The enemy advances, we retreat; the enemy camps, we harass; the enemy tires, we attack; the enemy retreats, we pursue.” They avoided annihilation in decisive engagements but continually fought as they fell back in orderly fashion from the regime’s months-long advances, preserving themselves for future guerrilla operations in Qalamoun once the regime declared ‘victory’ and re-deployed its forces elsewhere. However, Jabhat al-Nusra refused to follow the rebels’ plan of action, executing rebels who (correctly) retreated and accusing their brigades of taking bribes from foreign powers in exchange for losing the battle on purpose.

Daesh’s ‘liberation‘ of al-Raqqa from its liberators in 2013 was due principally not to collusion with the regime but to this same rebel disunity. Each faction and brigade was confronted and eliminated one by one by Baghdadi’s gangs who then applied this strategic template all over northern Syria in 2013, opportunistically isolating and picking off rival groups, commanders, and towns even as they collaborated with these same groups in anti-regime operations such as the seizure of Menagh airbase. They took advantage of the frictions between the secular-democratic FSA and the Islamist-democratic factions by relentlessly targeting the former while avoiding or collaborating with the latter. This fed Islamists’ illusions that Daesh were merely misguided Muslim brothers and fellow mujahideen rather than bearded Bashars and Kharijites.

The revolution within the revolution in January 2014 to overthrow Daesh in northern Syria was similarly stunted by rebel disunity. Factions that later coalesced as the Syrian Revolutionary Front led by Jamal Marouf and the Army of Mujahideen sprang into battle while the constituent elements of the Islamic Front were incoherent, some fighting, others avoiding combat. Ahrar al-Sham, whose commanders’ mutilations by Daesh provoked denunciation by the first Friday protest of 2014, initially held its fire. Its leader Hassan Abboud, who also heads the Islamic Front’s political office, offered to mediate with Daesh even as popular fury exploded against them in demonstrations and armed attacks. Only after the Daesh launched wave after wave of suicide attacks against Islamic Front’s Liwa al-Tawhid while rejecting mediation offers for weeks did the Islamic Front as a whole begin to fight them. This divided response undermined rebels’ momentum and allowed Daesh to retreat under fire from much of Aleppo province and bloodlessly evacuate Idlib and regroup in al-Raqqa and in eastern Syria/western Iraq. Failing to finish Daesh off gave them time to lick their wounds and prepare for a ferocious wave of victorious offensives in Deir Ezzor, western Iraq, and Kurdish areas of Syria that culminated in the declaration of a Caliphate in summer of 2014.

Overcoming disunity is the most important task facing rebel (and political opposition) forces. Without uniting those who can be united, it is impossible to pursue a common policy, impossible to respond coherently either to the regime or Daesh, impossible to forge effective leadership, and therefore all but impossible to win the war.

Only great unity can lead to great victory.

Rebel cooperation remains largely local and occasionally regional rather than national. After three years, rebels still have not established a unified command or even set up a national operations room. Doing so is essential for rebels to move beyond winning short-term tactical victories like the Kessab offensive in early 2014 to long-term strategic victories, the accumulation of which will destroy the regime. The regime’s national scope and operation along interior lines allow it to neutralize and eventually reverse locally and regionally limited rebel forces operating along exterior lines by quickly redeploying its forces and assets from one front to another. The only way rebel forces can counter this (since they fight along exterior lines) is through greater coordination, so when the regime makes a concerted effort to gain ground in Aleppo, rebels counter-attack in Latakia (for example). Until cross-front and cross-regional coordination develops, rebel tactical victories will continue to be nullified by the regime’s ability to win strategic victories and only by accumulating strategic victories can rebels regain the initiative in the war.

Amalgamating rebel forces — some 150,000 men divided among a handful of big coalitions and countless smaller formations — into a single army with a clearchain of command is probably impossible. Nonetheless, a national operations room to assemble an operationally albeit not ideologically cohesive coalition of coalitions could work if rebel commanders are willing to surrender some autonomy for the sake of greater coherence as a national fighting force. However, the experience of the Islamic Front shows how difficult uniting is in practice even with good faith commitment by constituent groups. As with any politically heterogeneous opposition formation, the moment the front takes a position or an action that is controversial, it leads to fitna which, more often than not, causes counterproductive splits. Army of Islam commander Zahran Alloush’s decision to suspend his army’s participation in the Islamic Front in response to the Islamic Front’s Revolutionary Covenant is but one example of this tendency.

Rebel unity is more urgent than ever given the second great schism among forces fighting the regime: the war Al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra launched in July 2014 to smash the FSA and carve out territorially contiguous theocratic emirates in Idlib and Daraa. Jabhat al-Nusra’s aggression was precipitated by ever-greater U.S. involvement on the side of the opposition and Daesh’s newly declared Caliphate, both of which threatened the Al-Qaeda project in Syria from different directions.

The Balance of Forces: Shifts and Underlying Trends

The single most important thing to understand about Syria today is that the pre-2011 political setup is gone forever. No force on Earth can reverse that. The battle now is over what will replace the old arrangements, over what new political superstructures and class relations will prevail. The outcome of this fight is nearly impossible to foresee even in general terms because there are so many warring factions:

o The regime (NDF, Syrian Arab Army).

o Foreign regime allies (Hezbollah, Iraqi and other foreign Shia militias).

o The rebels (FSA, Islamic Front, Syrian Revolutionary Front, independent Islamist and secular brigades).

o Foreign rebel allies (small groups such as Jamaat Ahadun Ahad or the Chechens who defected from Daesh).

o Jabhat al-Nusra.

o Daesh.

o The Kurds (the People’s Protection Units [YPG], a militia dominated by the secular-democratic and socialist Democratic Union Party [PYD]).

Some of the aims and interests of these actors overlap; others contradict each other irreconcilably. The regime, its foreign allies, and Daesh have benefited from the rebels’ failure to reconcile their serious differences with YPG and PYD for the purpose of uniting to smash the three enemies that menace them. Even worse, throughout 2013 Islamist and FSA brigades fought alongside Daesh as Daesh attacked the YPG. This strengthened the rebels’ enemy, alienated and weakened a potential ally, and deepened Syria’s fragmentation.

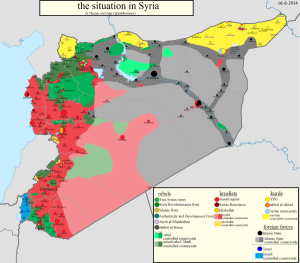

As of Aug. 1, 2014

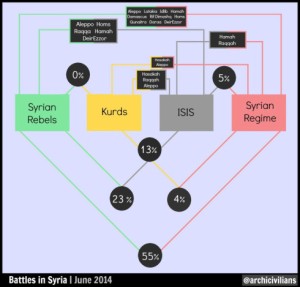

Since the regime and Daesh both focused almost all of their attacks on rebel forces in early/mid 2014 instead of on each other (Daesh-regime clashes constituted only 5% of the total battles fought in Syria in June 2014, for example), many activists and even the Syrian National Coalition of Revolution and Opposition Forces claimed that the two were partners or co-conspirators. What appeared to be conspiracy was really the result of strategic calculation born of a particular conjecture. For its part, the regime knew that the demographics of its strongholds made Daesh rule there all but impossible and prioritized fighting the rebels as the only force that could potentially generate enough broad-based support to supplant and displace it. Meanwhile, Daesh opportunistically preyed on the weakest actors on the political landscape — the scattered, divided rebel movement and the beleaguered institutions of bourgeois-democratic governance that arose in rebel-held areas. Riven by the competing priorities of fighting versus governing as well as internal dissension, rebel and opposition forces were no match for the united and better-led Daesh as they eliminated rebel factions first before suppressing civilian activism in al-Raqqa as well as Manbij, the birth place of Syria’s first labor union.

________________________________________

“Who do you feel best represents the interests and aspirations of the Syrian people?”

Region Regime Opposition Extremists

Total 37% 35% 13%

Damascus 59% 17% 0%

Tartus 92% 2% 0%

Latakia 71% 15% 1%

Idlib 4% 61% 24%

Aleppo 36% 36% 19%

Daraa 25% 43% 12%

Rural Damascus 31% 49% 5%

Homs 36% 32% 1%

Hama 31% 35% 18%

Suweida 37% 8% 0%

al-Hasaka 37% 32% 25%

al-Raqqa 12% 47% 37%

Source: Orb International.

________________________________________

The defeat of rebel forces has not given way to peace between Daesh and the regime but to an even more barbaric war between them, a war the regime is losing and will lose in northern and eastern Syria. This proves that Daesh was never a puppet nor a partner of the regime (or a creation of Iran, for that matter).

Since the battle of Qusayr in June 2013, the regime’s military momentum has masked the loss of its social and economic foundations. The old regime’s power peaked in 2011 and the post-revolution regime’s power — fueled by massive foreign support — peaked in mid 2014, checked by its own internal contradictions and by the growing power of Daesh.

The rebels’ military momentum lasted from 2011 until they entered Aleppo in mid 2012 and liberated al-Raqqa in early 2013, at which point their internal contradictions impeded further progress. Lack of unity, organization, and effective leadership prevented the rebels from securing the socio-economic foundations upon which to erect the kind of sturdy bourgeois-democratic state necessary to govern liberated areas and simultaneously wage a protracted and victorious revolutionary war.

This failure by the rebels led directly to the Daesh’s disastrous success. The revolution is the negation of the regime and Daesh is the negation of the revolution.

By seizing income-producing assets like oil fields, Daesh not only acquired the economic basis for a state even more fascistic than the Assad regime but — more importantly — prevented the rebels from becoming a self-financing force. This put the rebels at the mercy of the foreign agendas of foreign states who are the only social forces with access to the necessary money, arms, and support to sustain the civilian and military opposition. So unlike both the rebels and the regime, Daesh is economically viable and financially self-sustaining. This has profound implications:

1. No outside power has leverage over Daesh.

2. Daesh’s economic underpinnings mean that its inherent war-fighting capabilities are significantly greater than the inherent capabilities of both the regime and the rebels. “Endless money forms the sinews of war.” (Cicero)

3. Daesh’s rule will endure because its economic foundations are secure; the political monstrosity it is building unfortunately does not contradict but corresponds with its economic base.

Assad’s crumbling fascist edifice was torn down in much of northern and eastern Syria only for a more savage and firmer one to be erected in its place.

However, Daesh is not invincible; it has strong and weak points (or in other words, contradictions) just as its enemies do. Daesh’s weak points are less serious than those of rebel and regime forces and it has far more strong points than weak points compared to both of them which is why Daesh can beat them (and its Iraqi enemies) on many fronts simultaneously.

Daesh Strong Points:

o Unity and united, effective leadership.

o Allies abroad — none, save for a tiny proportion of the ummah.

o Fighters highly motivated by religious zealotry.

o Victory means defending its fortified strongholds (35% of the country).

o Fights along interior lines.

o Coherent governance and unified cultural and economic policies.

o Resources (financial, economic) — controls Syria’s agricultural areas and themajority of the oil-producing areas.

o Enough popular and tribal support for a stable regime.

o Continued inability of the regime and rebels to turn their weak points into strong points.

Daesh Weak Points:

o Unjust cause.

o Popular support based on rebel inability to provide security and stabilit yrather than ideological agreement.

o Manpower.

o High proportion (perhaps a majority) of its fighters are non-Syrians.

Daesh’s power has yet to peak and may not do so until U.S. President Barack Obama leaves office. Its leaders are careful not to over-extend their 20,000-man army, wise enough to attack only targets that have significant strategic value in situations where Daesh’s victory is not a gamble, and shrewd enough to mix force with diplomacy to secure the support of tribes in eastern Syria and Western Iraq. If Daesh’s leadership is more united, effective, and competent than that of the rebels, it because they they have been waging war uninterruptedly for almost a decade, long before protests broke out in Syria in 2011. Rebels and oppositionists must close this experience gap if they want a fighting chance at taking their country back from Baghdadi’s gangs.

The fate of the Syrian revolution was once in the hands of doggedly non-violent grassroots activists, but today it is in the hands of men with guns and the foreign powers that back them. Now, war is the main form of struggle and army is the main form of organization. The armies of three sides — the regime, the rebels, and Daesh — are locked in a war of attrition and the side that is exhausted materially and spiritually first, loses.

The contradiction between the regime’s military superiority and social infirmity will not last forever, nor will it end soon; it is a process of unravelling that will take years rather than months. Militarily inferior rebel and opposition forces are, in many respects, in worse shape socially than the regime as small numbers of (unpaid) rebels quit the battlefield for the sake of giving their families some normalcy after three long years of hellish war and as increasingly depopulated neighborhoods buckle and submit rather than starve. At the same time, the only neighborhoods that have become safe for regime forces are those totally emptied of both people and rebels such as Homs; true submission on a mass scale continues to elude the regime despite its barbaric tactics.

As the increasingly exhausted regime fights to exhaust its opponents, the regime’s forces are slowly being ground to dust by a combination of its own unjust nature, aims, and methods, its manpower shortage, the rising power of Daesh, the determination of millions of revolutionary Syrians to persevere in their opposition to Assad despite unimaginable suffering, and the gradual escalation of U.S. support for rebel and opposition forces. If the rebels (and Kurds) can unite, they can take advantage of these factors that work in their favor to break the war’s strategic stalemate which will force the regime to choose between holding one city or military base at the expense of losing another. As retreats and defeats mount, Assad’s rump regime will fragment and conditions will ripen both for palace coups and for a second revolution.

You won’t hear this on the daily news feed.

‘In 2003, when the United States went and bombed Iraq in the “shock and awe” campaign, it opened the door for various al-Qaeda people to come in and join the insurgency, including Mr. al-Zarqawi, who came from Jordan, formed al-Qaeda of Iraq, created mayhem, introduced a very virulent form of sectarianism, and of course beheadings and suchlike.

‘And it’s out of al-Qaeda of Iraq that the Islamic State of Iraq was born. When the conflict opened up in Syria, they expanded their name to the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria. So this organization is a product of the Iraq War. ‘

Vijay Prashad

LikeLike

al-Qaeda existed before the Iraq war. The fact that they recruit from anywhere would indicate that those countries with the largest sympathetic population would have the largest amount of members. The amount of fighters in any one particular country of course depends on the geography and Iraq is pretty close to Syria so no surprises there. The fact that the Iraq war brought on the spring uprisings is a good thing. The fact that in those revolutions there would be many vested interests involved was expected. It may take some time for those countries to evolve to the democracy we experience. The groups involved would always be involved, Iraq war or no war but the spring uprisings may have taken a lot longer to eventuate without the Iraq war.

LikeLike

‘It may take some time for those countries to evolve to the democracy we experience.’

Yes, perhaps 100 years, unless China can sort it out. The West has failed miserably up to date, this new adventurism will at least give them a chance to test their weapons systems against bandits, international pariahs.

LikeLike

think it will set things back 100years if china is involved. It won’t be up the west it will be globalisation and the response to it from the peoples in those countries and it seems to me we are off to a pretty good start and at this rate it should be sooner rather than later that things sort themselves out. 100 years in the scheme of things isn’t that long but the rate of change in all fields would indicate a much faster timeline.

LikeLike

The Middle Eastern peoples will not reconcile their differences quickly, superstitious nonsense is embedded on the hard drive. There maybe uprisings against oppression, as in Egypt, but sadly it comes to naught.

LikeLike

everyone was superstitious at some time and china is full of it, however it is changing in china and in the middle east as economic development pushes things forward the same as it did in the west

LikeLike

China is deity free, this is a great leap forward.

The new technologies are no guarantee of peace, so tackling the middle east problem will require a revolution in thinking. For instance, Xi could make the point that on the evidence available we are not alone in the galaxy.

LikeLike

china is not deity free it is full of superstition. Anyone could make the point we are not alone in the galaxy. Xi could make the point despots are not alone on the planet as long as he is here. Economic change brings a revolution in thinking and it is economic change that will bring revolution to the middle east and Africa. Xi will do whatever he can to stop that because he knows the more countries that have revolutions against despots the more isolated he becomes.

LikeLike

Taoism has had a big impact, but is relatively harmless in comparison to those who worship an omnipotent god.

‘Hundreds of millions of Asians – from China, Taiwan and Hong Kong to Singapore and Indonesia – worship the gods of Taoism. It is a faith that has melded the teachings of erudite philosophers with traditional fables, the rituals of secret societies, magic, alchemy, psychology, rural superstitions and even lovemaking techniques into an esoteric canon that is very much alive today.’

Andreas Lorenz

LikeLike

Chinese authorities appear to have a nasty fascist streak.

‘The state-run Beijing News said that the Modern College of Northwest University, located in Xian, had strung up banners around the campus reading ‘Strive to be outstanding sons and daughters of China, oppose kitsch Western holidays’ and ‘Resist the expansion of Western culture’.

‘A student told the newspaper that they would be punished if they did not attend a mandatory three-hour screening of propaganda films, which other students said included one about Confucius, with teachers standing guard to stop people leaving.’

Daily Mail

LikeLike

Any ruling clique that is into ‘harmony’ is likely to have a nasty fascist streak and the ‘harmony’, as with the three hour watching of propoganda films, is imposed and not the result of free choice. There is a part of me that is delighted that the students had to be forced tho watch something valorising Confucian thought as the idea that they flocked willingly to see such a film would be prettyvomit inducing. As Mao so astutely pointed out that if the reactionaries take over (which they have) they will know no peace.

LikeLike

Newman attacks the Left.

http://joannenova.com.au/2015/01/maurice-newman-conservatives-outsmarted-they-apologise-where-they-should-demand-apologies/#more-40502

LikeLike