The Westminster Declaration

We write as journalists, artists, authors, activists, technologists, and academics to warn of increasing international censorship that threatens to erode centuries-old democratic norms.

Continue readingWe write as journalists, artists, authors, activists, technologists, and academics to warn of increasing international censorship that threatens to erode centuries-old democratic norms.

Continue readingBarry York

Fifty years ago, on 11 September 1970, a group of 70 students at La Trobe University assembled on their campus for a protest march against the American war in Vietnam. I was one of the organisers. It was an unusual protest march in that its route was along a suburban street in West Heidelberg, Waterdale Road, which ran off the campus grounds. The street consisted of a light industrial section and residences, including housing commission homes.

The 70 of us were a motley crew of Maoists, anarchists, and Christians and our objective was to march five kilometres to the Ivanhoe shopping centre, give out leaflets promoting the second Vietnam Moratorium scheduled for the 18th September, and then march back to the campus. The first Moratorium, on 8 May that year, had been a resounding success, with about 100,000 participants in Melbourne.

History is full of surprises, twists and turns. We had no idea that our poorly attended, local, march would become a cause celebre – thanks entirely to the violent, repressive, behaviour of the police.

The march had not progressed very far when police cars arrived and blocked the street. A plain-clothed Special Branch policeman jumped out and gave the order: “Batons! Break it up!” The police laid into us, not just with batons but with fists and boots too. We tried to flee back to the campus and made it to a wide paddock (today the asphalted carpark of Chisholm College) but the police pursued us on foot and in their cars.

It was a shocking and frightening experience and I think it’s to our great credit that we were not intimidated. Instead, we rallied in the central square of the campus and, with our trusty megaphone, informed students who gathered from the library, cafeteria and colleges about what had just happened.

****

A general meeting resolved to organize another march along Waterdale Road, this time from Northlands shopping centre, two kilometres away, to the campus. We figured that the police would let us march, given that we were marching to the campus. We were not out to block the street and welcomed independent observers, such as the university chaplain, Ian Parsons.

The second march, attended by about 400 students, took place on 16th September, and on this occasion the media were also in attendance. Everything seemed fine – until we came to a section of the street that narrows at the industrial area just before the campus.

There is no doubt that the police had made a decision to attack the demonstration at that part of the route. They were well prepared with larger numbers and with particular student leaders as their targets. In a letter to the dailies, Ian Parsons expressed his ‘disgust at the behavior of the police’.

A conservative group, the Moderate Student Alliance, reported that, ‘There had been absolutely no provocation’.

The inspector in charge of the police riot, Platfuss, told a reporter: “They got some baton today and they’ll get a lot more in the future”.

Such violence on the part of the state was not new to those of us who, by 1970, were seasoned protestors. But what was surprising was that it was so openly political. They could have just let us march back to the campus, as we had nearly completed the route. Instead, they waited in ambush just a block from the university grounds. Nineteen students were arrested that day, on 16th September, and many were punched, kicked, batoned and injured by police.

Another surprising, and worrying, aspect was the use of guns to make arrests. I know of no other protest marches of the Vietnam period in Australia where police made arrests at gunpoint.

Again, we sought refuge by running to the campus but again the police pursued us. I was running across the paddock slightly ahead of a comrade, who I will call ‘Peter G’, when suddenly I heard the exclamation “Stop or I’ll shoot!” I glanced back and in the distance saw a policeman aiming something in our direction. I kept running but Peter G stumbled and was arrested.

Larry Abramson was arrested at gunpoint before the march had scattered. He describes what happened in the brief audio excerpt accompanying this article.

It is with a sense of pride that I recall how we again refused to be intimidated. A huge student general meeting resolved to organize a third march, an assertion of our free speech and right to protest.

The third march, on 23 September, received wide support and included representatives of trade unions. About 800 people marched defiantly along Waterdale Road, to the campus. The police were fully prepared to attack, with two busloads of constables, two carloads of Special Branch and mounted troopers. But they had clearly been given orders from on high not to do so.

On the third march, as we approached the campus, we took over the whole width of the street. The police tried to move us over but we stood our ground. The power of the people had won something vital to democracy, something that is not guaranteed in any laws but must be asserted: the right to march.

(Originally published on the blog of the Museum of Australian Democracy, Canberra)

Addendum:

Here are three youtube compilations respectively about the first, second and the third Waterdale Road demonstrations: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZLr7ac1Ht-s

One of the most positive qualities of the great upheavals of the year 1968 was the assumption that people had a right to free speech. No-one was going to stop us speaking out, no matter how offensive some people found what we had to say – and we definitely were not going to allow the state to determine what could and couldn’t be said. Governments had forced the issue by banning publications – to protect us from ourselves – ranging from seedy crime novels to DH Lawrence’s ‘Lady Chatterley’s Lover’.

On the university campuses that helped fuel the ‘cultural revolution’ of that time, it was never doubted that we should have a right to say what we thought on any topic. The global student unrest had been sparked in 1964 by the Berkeley Free Speech Movement, where students and staff defied the University of California’s regulations restricting free speech.

In the People’s Republic of China a similar movement led by the young was underway, with ‘Big Character Posters‘ pasted up on buildings and in streets criticizing reactionary authorities within the Communist Party of China. Mao ZeDong said that “The big-character poster is a very useful new weapon, which can be used in the cities and the rural areas, in factories, co-operatives, shops, government institutions, schools, army units and streets – in short, wherever the masses are to be found. It has already been widely used and should always be used.”

This was overturned in amendments to the Chinese Constitution in 1982, however, when reference to the right to produce Big Character Posters was removed.

One of my first defiant acts in ‘the Sixties’ took place in 1968, my final year at high school in Melbourne, when I unlawfully distributed to my fellow students a banned publication exposing US war crimes in Vietnam. I forget the exact title but it was banned under Obscene Publications legislation. I was very nervous giving out copies at school, without being part of any organised radical student group, as I was isolated and worried about getting into trouble – especially for distributing ‘obscene’ literature!

In my first year at University, in 1969, the free speech question again arose: a contingent of La Trobe students, organised by the Labour Club (not to be confused with Labor Party!), went to Melbourne’s City Square to defy with other protestors the Melbourne City Council’s bylaw 418, which prohibited the distribution of literature in the Central Business District. The bylaw claimed to be neutral but was really an attempt to suppress the handing out of leaflets opposing the US and allied aggression in Vietnam.

There is some irony in the fact that 50 years later, the assumption that individuals should be free to say what they think is in reversal. Groups who may think of themselves as ‘left-wing’ or ‘radical’ today seek to do what the overt right-wing reactionaries of the 1960s did: namely, protect us from ourselves in the interests of cohesion and harmony. It’s scary stuff – or should be. And especially worrying when it happens on campuses, usually through collusion between official student representatives and University authorities.

Perhaps Australia would benefit from its own version of the UK’s Free Speech University Rankings (FSUR), which are conducted by the on-line group, Spiked.

Spiked has just published its fourth annual report, and it shows that campus censorship isn’t going away. Their survey, ranking 115 UK universities using a ‘traffic-light system’, shows that 55 per cent of universities now actively censor speech, 39 per cent stifle speech through excessive regulation, and just six per cent are truly free, open places. What’s more, in some areas, the severity of restrictions seems to be increasing. The FSUR survey found that almost half of all institutions attempt to censor or chill criticism of religion and transgenderism. It concludes that ‘There are blasphemies on campus, new and old, that students commit at their peril’.

The spirit of 1968 – a spirit that boils down to the right to confront and engage in the open exchange and debate of ideas – in a word ‘to rebel’ – is in urgent need of revival, especially if the next global capitalist crisis is ‘the big one’.

The late 1960s to early 1970s were years of success for the Left precisely because we created a milieu in which reactionaries in power and within the movement could be exposed and challenged. There was meaningful debate about what it meant to be left-wing, set against the context of real struggle. We challenged the old revisionist farts of the Communist Party of Australia as well as the old conservative farts of the Coalition Government.

I commenced this post with the words “One of the most positive qualities”. It would not be accurate to say that the whole cultural and political movement from the late 1960s to the early 1970s in Australia, with its many factions and outlets for expression, was consistently imbued with the ‘free speech’ ethos. And after the movement’s quick decline, an authoritarianism set in – among some/too many (though not all) – that ran counter to the earlier rebellious ethos. At its worst, some of us turned into our opposites. I personally regret that very much. It applied to me, too – but not everyone. It’s what happens when you stop thinking and become obedient, a follower rather than a critical thinker. You can be obedient to the state or to the gods or God – or, in my case, to a party leadership. Big mistake.

There were some terrific – poetic – slogans from the French student-worker uprising of 1968. “Il est interdit d’interdire”! “It is forbidden to forbid” represents a certain spirit. Of course, if it is dissected clinically, one can immediately think of flaws and exceptions: is it forbidden to forbid murder? But it is the spirit of that slogan that mattered back then. And still does.

“It’s a strange world when the most conservative people on earth call themselves ‘progressives’ and no one bats an eyelid” – email from Bill Leak, 4-10-15

“These people are trying to take us down the road to fascism. It might be nice, PC, inclusive, compassionate, non-gender specific smiley-face fascism but it’s still fascism” – email from Bill Leak, 30-10-16

****

I had the privilege of becoming one of Bill Leak’s friends. We corresponded, sometimes in substantial emails, and chatted by phone. We never met, but wanted to.

I did not agree with all his cartoons, needless to say, but defended his right to express his views via his excellent technical skills, brilliant intellect and wit, powerful way with words and awesome imagination. In terms of political philosophy, I had very little in common with those on the Right who supported him – other than a shared, stated, commitment to free speech.

And I didn’t agree when he would use the term ‘the Left’ to assail his opponents. It was understandable that he would regard the censorious reactionary creeps who John Pilger and Andrew Bolt both agree are ‘the Left’ as actually constituting some kind of left. After all, where is the alternative – a genuine Left – in public discourse? But I managed to point out to him that the Left is not defined by self-labelling, or by the right-wing media, or by some dogmatic formula into which reality is forced, but rather by long-established values and theory, and politics based on the ever-changing real world.

In an article Bill wrote defiantly for ‘The Australian’ after being summoned before the Human Rights Commission, he again attacked ‘the Left’. I emailed him, arguing that “such types have nothing in common with Marx’s rebellious spirit, let alone revolutionary political philosophy, and the term ‘pseudo-left’ and ‘faux-Marxists’ needs to be popularised”.

Bill’s response:

“Thanks SO much, Barry. If ONLY I’d spoken to you while writing it. I squirmed in my chair for a fortnight but couldn’t come up with the terms pseudo left and faux-Marxists and now it’s too late”.

****

Our contact began when I wrote to him, three or four years ago, to congratulate him on an excellent cartoon in ‘The Australian’, attacking a union boss who had been dog-whistling about ‘foreign workers’. As a leftist influenced by Marxism, I knew there was no such thing as foreigners when it came to the working class. I told Bill. He agreed.

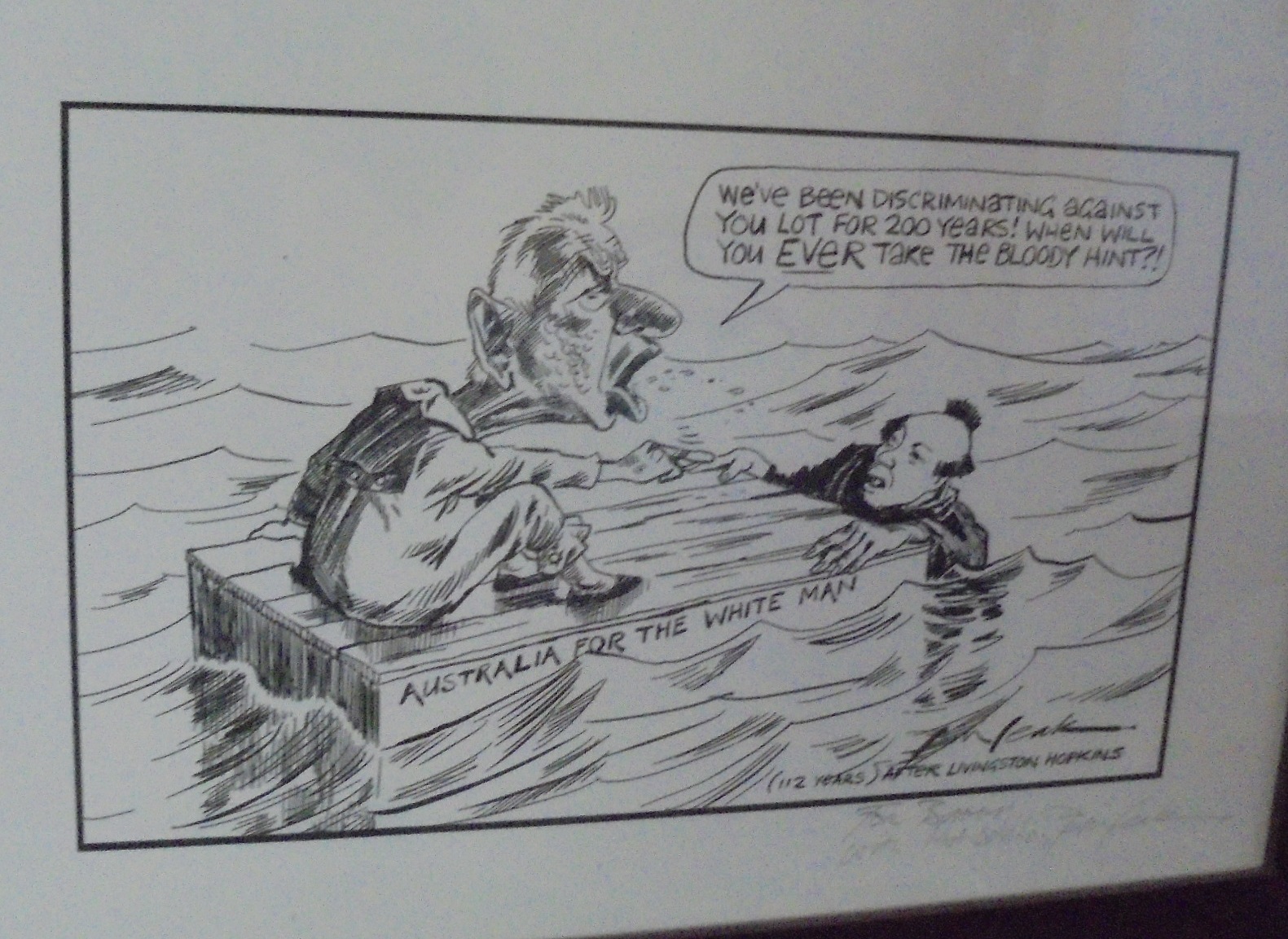

Foreign workers’ cartoon… (112 years) after Livingston Hopkins…

He had an indomitable sense of humour and wit. Early in 2015, when very serious death threats were made against him by Islamo-fascists, he had to uproot his family and move house and studio at short notice, and adopt a false name. Armed protection had to be arranged for him and his family. His crime had been to portray a figure in a cartoon that resembled Muhammad. It was not gratuitous stuff, but a response to the murder of cartoonists in France.

“Je suis Charlie’. Remember?

Bill’s response to me, in an email was:

“In much the same way that it takes a bit of time before you can laugh at tragedies, it might still take a while before Goong [his wife] and I can laugh about all this upheaval. I feel pretty sure though that it won’t be long before I’ll be able to say, “You remember that day when I woke up with a roaring fatwa? Best thing that ever happened for both of us.”

He continued:

“It is of course galling to read the letters in the paper from people “daring” me to “dare” to draw a cartoon that may offend Muslims in the way Saturday’s cartoon appears to have offended some of the more humourless Christians. It’s not as if I can write a letter myself, demanding they go back and check the cartoon from January 10. I’d love to tell them it resulted in me having to find a new home and live under an assumed name because the people I’d “offended” wanted to square things up by tracking me down and cutting my head off but, for obvious reasons, the less people know about it the better.

“Right now the thing that worries me most is the prospect of discovering I’m being targeted by Evangelical Christians, wanting to turn up at my place in a mini-bus and stand around on the front lawn strumming guitars and singing songs at me.

“One fatwa at a time, please!”

State censorship and the spirit of ’68…

As someone radicalised in the 1960s, who still regards 1968 as the Left’s finest year and high point internationally, I saw in Bill’s spirit and many of his cartoons the long-lost spirit of that year: its irreverence, rebelliousness, defiance and challenge to the dominant ideology (what we today call ‘Political Correctness’ – yes, it was around back then but in an openly right-wing form).

Much of the censorship back then was undertaken by the state under the guise of clamping down on obscenity. There was an Obscene Publications Act, which banned art and writings that members of a Vice Squad regarded as sufficiently pornographic for them to physically remove them from bookshops. If a magistrate shared the Vice Squad’s view, then the literature was banned.

Publications exposing US war crimes in Vietnam were also banned under the Obscene Publications Act. At high school, I unlawfully distributed the banned pamphlet, ‘US atrocities in Vietnam’ (I think it was called that, from memory).

The attempt at state intimidation and censorship that Bill Leak experienced, and fought, was undertaken via ‘human rights’ legislation: the Racial Discrimination Act. Go figure. And see the Appendix below for Bill’s email of 30-10-16 as to why and how the cartoon sought to support Indigenous people in remote communities and was not racist.

Every society has a dominant sense of what is right and wrong, what is fair comment and what is going too far, but the real question concerns the parameters as set down by the state, by official censorship.

That action could be taken against a cartoonist in the C21st by an arm of the state – and let’s not be coy about it, that’s what the Human Rights Commission is – showed that the parameters are way too broad and censorious. Even the Greens Senator, Nick McKim, stated on national television that he felt Bill’s controversial ‘Dear old dad’ cartoon was exempt under Section 18D of the Racial Discrimination Act (which basically exempts on the grounds of ‘fair comment’).

‘Dear old dad’ cartoon…

Bill tapped into a mood of resentment on the part of many people who grew sick and tired of being smugly admonished by their finger-prodding ‘betters’ in the Establishment that they should not do this or that, or think ‘like that’. This is not to suggest that those feeling resentment are always right, they are not, but the culture of Political Correctness has made nuance almost impossible. You either toe the line entirely or you are racist and any variety of ‘phobe’. There is little room in this culture for debate, for the open clash of conflicting ideas. In this context, ‘Being offended’ has become an argument – a case for opposition to something – rather than just a subjective feeling.

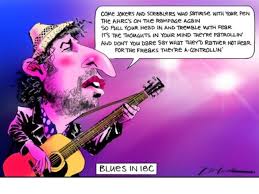

Punching up… at the cultural establishment

Those who accused Bill of ‘punching down’ have it upside down. His cartoons in the main were actually punching up, challenging those at the top, the decision-makers, those with great and sometimes dominant influence in the media, the senior bureaucracy, bourgeois academia, the ‘aristocracy of labour’ (or ‘union bosses’ as we described them in the communist party) and mainstream politicians of all stripes who, in general, prefer to deny or obfuscate life-threatening problems and restrict civil liberties. It takes a weird sense of victimhood – a denial of human agency – to see it the other way ‘round.

No other mainstream cartoonist so incisively mocked the Green quasi-religion. His ‘Christine Milne’ sitting self-righteously with the fairies at the bottom of the garden, in vivid unreal technicolour, was among my favourites.

Green fairies at the bottom of the garden…

No other cartoonist so effectively challenged economic protectionism. None so willingly revealed the absurdity of all the religions, including the quasi-religious totalitarian impulses of the reactionary pseudo-left. None so courageously stood up to the current brand of ‘clerico-fascism’.

He will be best remembered for his defence of free speech. He stood up to fascists, at great personal cost. To me, regardless of the cartoons with which I disagreed, those qualities make him a cultural hero.

I’m devastated by his death, and disgusted by the attacks he endured from what passes for ‘the left’ today, by the state and by Islamo-fascists.

Bill, thank you for your work, and for having me as a friend. And for your spirit, the best long-term hope for which is the revival of a genuine left.

* * * *

Appendix:

Bill’s email of 30-10-16 on why his ‘Dear old dad’ cartoon was not racist:

Sorry I didn’t reply to your previous email that arrived just a few days after I received news I was about to be hauled before the Inquisition. Since then I’ve discovered drawing cartoons and fighting the dark forces of tyranny at the same time is bloody hard work and doesn’t leave me with much time to spare for writing emails.

I have to give my cartoons names when I put them up on the website and the name I gave the one that’s caused all this latest trouble was “Dear Old Dad”. Well, dear old dad is having one hell of an impact. I hoped it would prompt people to take a good, hard look at the plight of aboriginal kids in remote communities but it seems that’s something so confronting they prefer not to look at it at all. So much easier to accuse me of racism for having brought the subject up. It’s pleasing to see, though, that finally the virtue signallers are running out of abuse to hurl at me and the conversation is starting to focus on the little boy in the middle of it and his indescribably sad, desperate life. The cartoon was supposed to be about him after all, for Christ’s sake. Col Dillon (Anthony’s father) [both of Indigenous ancestry] rang me on the morning of the day it was published to thank me and congratulate me for doing it. He knew what I was trying to say and knowing he was glad to see I’d tried to say it clearly was good enough for me.

I grew up in a place in the bush called Condobolin among aboriginal kids. When I went back there in 2001 (for the first time in over 30 years) it was depressing to see how much worse things were for the indigenous people than they were in the 60s. Intergenerational welfare dependency is like a slow working poison. Killing with kindness is just the ticket I suppose if, deep down, what you really want to do is discreetly eradicate a population while simultaneously parading your compassion and telling everyone how much you care.

To tell you the truth I had no idea dear old dad would also trigger a debate on 18C, let alone that I’d end up at the pointy end of a battle to get it amended or (dare I hope) repealed. Two shitfights for the price of one! Perhaps by now Southpommasane and Triggs might be regretting they decided to try to rid themselves of this turbulent cartoonist. But they did, and I’m going to fight like buggery. It’s just as well I like a blue, Barry.

These people are trying to take us down the road to fascism. It might be nice, PC, inclusive, compassionate, non-gender specific smiley-face fascism but it’s still fascism. And if that’s where we end up the Triggses and Southpossums and all their fellow members of ‘the new monocled top-hatted elite who hold the workers in disdain for their consumerism’ won’t know what hit them. – Bill Leak, 30-10-16

The following 22 minute edited excerpt from an interview I recorded with Ted Bull (1914-1997) between 1988 and 1990 recalls Ted’s memories and reflections on the Free Speech movement in Brunswick, Melbourne, in 1933. The struggle is commemorated today by a monument in Sydney Road, Brunswick, but the lessons – the need to defend and assert free speech – remain valid.

Ted Bull was arrested on the free speech protests. As he recalls: “You’d get half a dozen words out and you’d be arrested. Not only arrested but the coppers would take you behind the Town Hall and they’d give you a bloody ‘doing over’ – and a good ‘doing over’ too”.

For overseas listeners, a “stump” in this context refers to a spot where a speaker regularly set up – usually a street corner – to speak to passers-by. Crowds would gather and this was seen as dangerous by the state at a time when communist ideas were gaining support. Also, when Ted refers to “the hook”, he means his work as a waterside worker – or ‘wharfie’ – in the days before widespread mechanisation when much of the work was manual and sacks were carried using a hook.

At the time of interview, I had no idea that someone had been shot during the free speech struggle in Brunswick, which happens to be my ‘hometown’. Ted talks about ‘Shorty’ Patullo who was shot by police and hospitalised. It was also surprising, though shouldn’t have been, to learn that in addition to the police it was die-hard Labor Party supporters who would disrupt the stumps.

The 1933 struggle is probably best remembered for the makeshift cage in which Noel Counihan (1913-1986) locked himself in Sydney Road in order to give his speech without being arrested.

The above is a 22 minute edited excerpt but the full interview runs for about 20 hours, based on a whole-of-life approach, and is available in full via the National Library of Australia’s on-line catalogue.

workers' struggles and scientific socialism

Voices From the Periphery

A blog for popular culture, social history and politics from Mark Cunliffe

Get Lost

Melbourne Art & Culture Critic

a blog on popular struggles, human rights and social justice from an anti-authoritarian perspective

"We are sorry for the inconvenience, but this is a revolution"

A blog for social policy discussion and debate

A Blog Devoted to Socialist Economics

The Art and Craft of Blogging